Technology value selling

How to identify, define, and explain AI and other technologies' value in Board-relevant terms using a universal technology value taxonomy.

Part 1 of the Value Lifecycle Project

CIOs, enterprise architects, technology consultants, and software sales executives must persuade business leaders to invest scarce capital in technology projects versus other options. Each functions as a "value seller" in practice if not in title.

The latest cutting-edge AI and other technologies' features and functions are only a means to an end—a business value end. Technology sales executives and in-house IT leaders lose sight of this at their peril. Hence, the need for value selling.

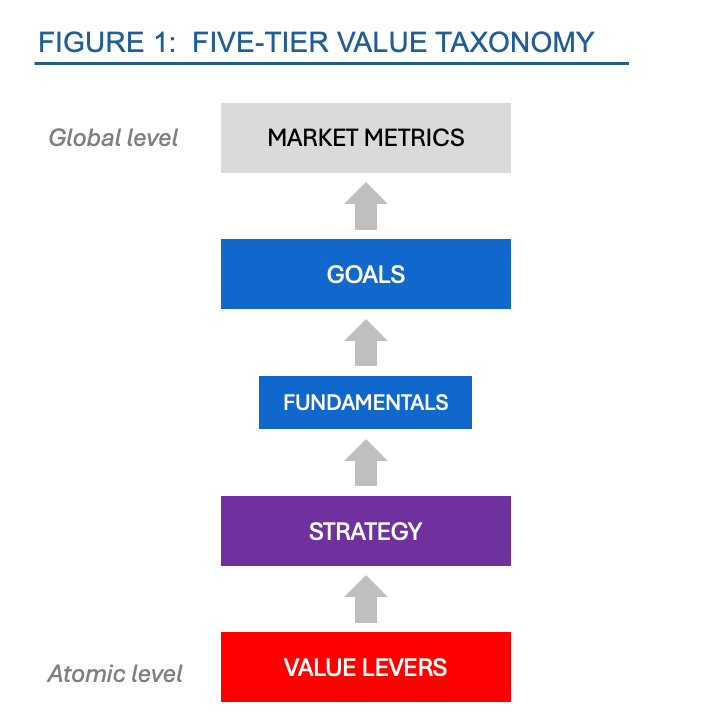

Technology value selling is the art and science of clearly articulating the causal model of how atomic-level value levers contribute to and enable improvements in firm market performance. Value selling requires the ability to clearly, logically, and defensibly articulate the five-tier value equation (Figure 1) of how—and how much—a technology contributes to firm strategies and outcomes.

At their core, all technologies provide three value levers that, when applied appropriately as part of organizational strategies, deliver measurable, Board-relevant value.

This paper provides a universal technology value taxonomy1 to help technology value sellers identify the full breadth of technology's value contribution potential and articulate it in a logical value equation suitable to persuade business leaders to invest scarce capital in any technology initiative.

Why buy any technology?

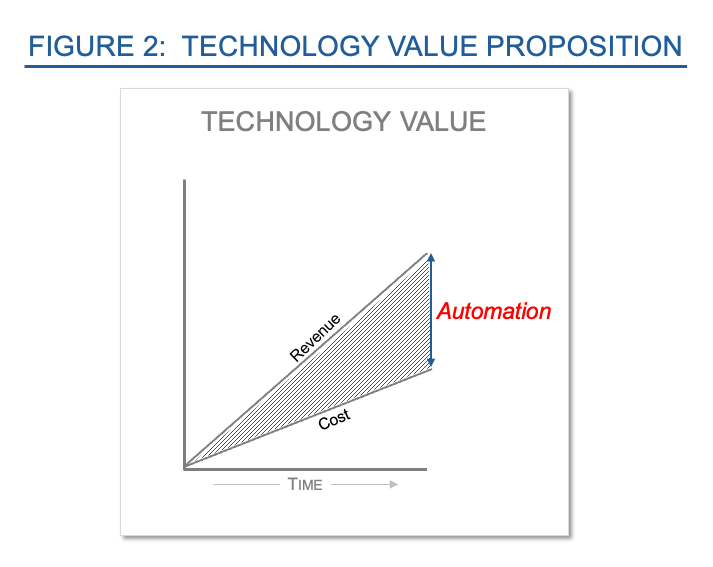

Of all the investments business leaders could make with their scarce time and capital, they invest in technology because they bet it will allow revenue to grow faster than costs (Figure 2) more effectively than other options.

Technology’s value levers

All technologies — hardware, software, and, AI — do three things at base (Figure 3):

That’s it. That is all any technology ever does, be it a network router, a relational database, middleware, an ERP system, sundry types of automation with code, or an AI decision model.

These three elements are levers. By themselves, they don't create value.

When applied properly, they help achieve desired outcomes (like other forms of leverage, such as a crowbar to move a boulder or credit to fund a new business). Where and how these technology levers are applied determines their value contribution.

Business strategies

Every business C-suite articulates strategies for improving firm performance. "This year we need to focus on...". These strategies appear in annual reports, 10-K filings, investor calls, and in the internal presentations that leaders use to provide direction to and motivate employees.

While terminology varies, all strategies can be mapped to four standard categories (Figure 4):

Agility/Speed: Execute existing processes faster and/or become more nimble to quickly adjust to changing market conditions

Productivity: Efficiency by another name—producing more value per unit of labor (and labor cost)

Quality: Improving first-time-right output, reducing time, effort, and cost spent on rework and recovering damaged customer relationships

Experience: Improving customer service to increase retention and upsell potential, or enhancing employee experience to increase motivation and discretionary effort while reducing unwanted attrition.

These four universal strategies are articulated by managers regardless of market conditions or where the firm sits in its lifecycle. Leaders of profit-seeking firms will draw on one or more of these to define their current strategy for achieving business goals.

Importantly for value selling, technology value levers are central to implementing all strategies. Each value lever directly or indirectly supports each strategy, often in overlapping and complementary ways:

Removing non-value-added work:

Allows firms to respond faster and creates time to develop new products or react to issues more quickly

Directly improves productivity as more can be accomplished with the same labor costs

Improves quality by eliminating tasks susceptible to human error

Enhances customer experience through faster, higher quality outputs and improves employee experience by eliminating tedious work.

Reducing opportunities for error:

Improves first-time-right quality of products and processes

Speeds execution and reaction times by reducing time spent fixing errors

Enhances productivity by reducing time and costs spent on error correction, paying fines, or issuing avoidable discretionary discounts4

Improves customer and employee experiences when "things work as expected."

Reducing cycle times:

Completes work faster, freeing staff to focus on other projects

Increases productivity by producing more value units in the same work period

Improves quality through faster error discovery

Enhances customer and employee experience through faster delivery and completion.

As evident above, each technology value lever contributes to each universal firm strategy in complementary and often overlapping ways.5

Business strategies are designed to improve business fundamentals

Strategies are expected to "move the needle" on one or more of three firm operating fundamentals:6

Revenue: Dollars received for the sale of goods and services

Risk: Risk is cost that hasn't yet hit the ledger—formally defined as the probability of an adverse event multiplied by its impact (cost)7

Cost: Cost of goods or services sold (COGS) and sales, general, and administrative costs (SG&A).

Each strategy contributes to these business fundamentals (Figure 5):

Agility/Speed enables firms to react to market changes more quickly, capturing new revenue opportunities and adjusting cost structures

Productivity directly improves COGS and SG&A costs, which can be captured as profits or reinvested in growth opportunities

Quality reduces risk (future costs) and may deliver secondary benefits such as higher customer retention revenue

Experience improves customer revenue and reduces customer and employee churn and associated retention or replacement costs.

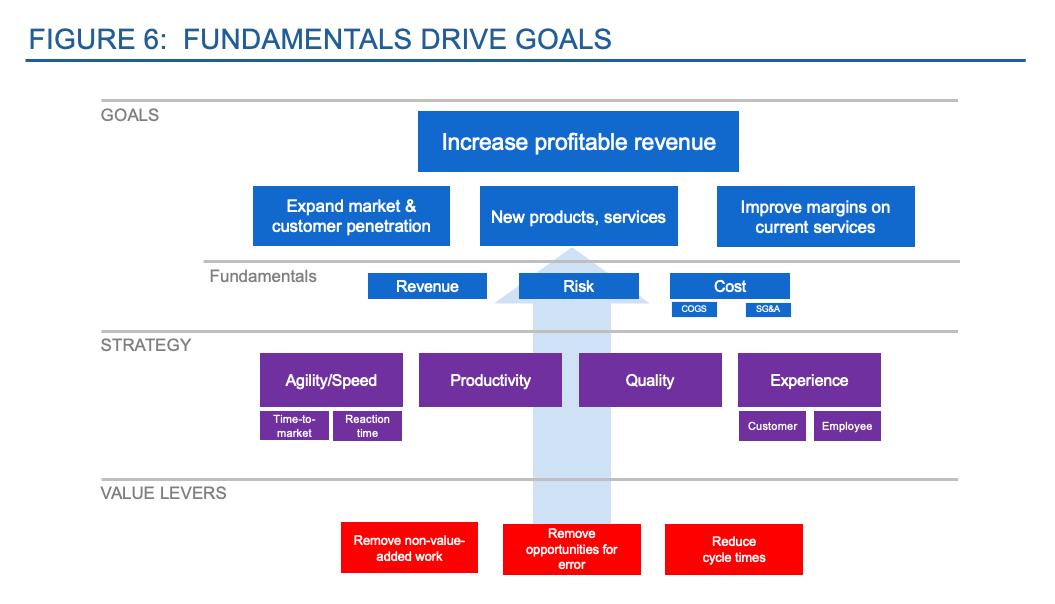

Improved fundamentals allow for delivering on C-suite goals

Ultimately, all strategies aim to increase profitable revenue. This additional profit (cash) can drive C-suite strategic goals (Figure 6):

Expanding into new markets or geographies, or penetrating deeper into existing customer bases

Investing in new products and services to generate future revenue streams

Improving margins on current offerings, returning value to shareholders as dividends and/or retained earnings.

Achieving C-suite goals improves market-level metrics

Increased profitable revenue drives the market-level metrics shareholders watch most closely and that often determine executive compensation (Figure 7).

Technology value contribution humility

Technology sellers must clearly articulate this five-tier (Figure 1) contributory linkage: from the technology's value lever contribution to strategy, to the strategy's delivery of fundamentals, to achievement of goals, to improvements in market-level metrics (FCF, EBIT, EPS) that shareholders value.

However, technology sellers should exercise humility and demonstrate understanding of the buying executive's perspective: Technology alone does not deliver top-line value.8 It remains purely a cost unless other contributing factors align. Technology is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for delivering Board-relevant value.

Sophisticated, empathetic value sellers recognize what buying executives already know: a complex combination of people, process, technology, and data requirements and risks determine the success of technology-enabled programs. The buying executive must mobilize budget authority, political capital, and personal time—along with that of key lieutenants—to realize the technology's value potential.

Technology is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition to delivering Board-relevant value.

Remember, your technical solution is not the only option. Your solution's value is relative to all other ways the buying executive could allocate scarce capital and time. Often, "doing nothing" is the strongest competitor, as the executive may see her time and political capital better spent elsewhere.

Beyond the value equation, value selling requires the essential skill of demonstrating experience, competence, and commitment to supporting the buying executive throughout the entire value realization journey.

AI and generative AI's impact on value selling

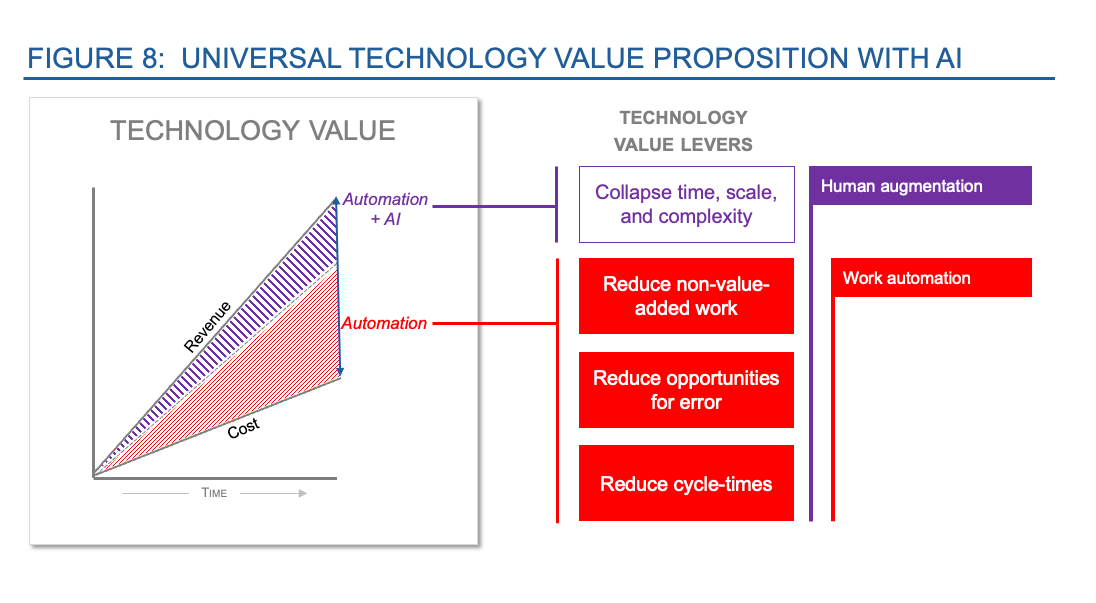

While AI and especially generative AI generate significant attention, there is no fundamental difference in this latest generation of technology's value equation.

Analysts often distinguish between work automation (replacing human work with machine work) and work augmentation (supplementing human work with machine capabilities). This distinction helps convey operational, process-level, and job-level impact differences, but from a value selling perspective, they are not materially different.

Various AI implementations collapse time, scale, and complexity barriers that no number of humans could overcome, but this fundamentally serves as an accelerant function of the three base value levers (Figure 8).9

Bringing it all together

Savvy technology value sellers (CIOs, enterprise architects, technology consultants, software sales executives) understand the often loosely coupled linkages between their technology's value levers and the ultimate delivery of C-suite goals. They articulate the causal model linking value levers to strategies, to fundamentals, to goals, to market metrics in a defensible value equation.

The value seller can "lead the witness" C-suite buyer by defining the value equation and suggesting contributory components and their weights. Ultimately, however, the buying executive must viscerally believe both the value equation and her ability to effect the required organizational change.

Help C-suite buyers define the value equation, but let them determine the variables to calculate the expected value. Use nudges and challenges rather than assertions.

Summarizing the key points:

Understand the firm's strategies

Understand how your technology enables those strategies

Define the level of contributory value, in all its variety, your technology offers

In the value selling context, AI's value proposition is no different than any other technology

Look beyond narrow labor cost efficiency within one budget line; often second-order value contributions such as risk reduction or quality improvement may be more valuable to the C-suite than direct labor cost reductions

Link the strategy to the firm's overarching fundamentals and goals

Articulate the linkage throughout the value chain, but don't overstate your technology's contributory value to C-suite goals

Help C-suite buyers structure the value equation and provide guidance, but don't prescribe the actual higher-level variable input values and weightings

The non-"hard dollar" value sell is partnership to ensure the technology-enabled program succeeds; your technology may be an excellent "crowbar," but the executive is more concerned about who will use it and whether they will use it properly to move the rock without causing collateral damage

Remember: features and functions are merely means to the end of value.

Summary

CIOs, enterprise architects, technology consultants, and software sales executives each function as a "value seller" in practice if not in title.

Technology value sellers must persuade business leaders to invest scarce capital in technology projects rather than other options. All technologies provide three fundamental value levers that, when applied appropriately in support of organizational strategies, deliver measurable, Board-relevant value.

Technology value selling is the art and science of clearly articulating how technology value levers advance corporate strategies, goals, and financial metrics.

The universal technology value taxonomy (Figure 7) provides the conceptual framework for any value seller to identify and model technology value potential.

Future articles will address how to credibly identify and quantify value claims and how to design and manage transformation programs for value realization.

Taxonomies are systems of hierarchical classifications and relationships.

Derived from Michael Porter's "value chain" concept, where successive activities add incremental value to a work-in-process product. Non-value-added work is required due to suboptimal workflow and tooling design but adds no incremental value to the end product.

Opportunities for error" is a Six Sigma concept related to quality. Poor quality (errors) cannot occur if the process eliminates the opportunity for—typically human—error.

Which, of course, lowers COGS and SG&A costs.

A word of caution: Because one technology can provide value across three atomic value categories (the value levers), value sellers must avoid double-counting value contributions. Improved quality reduces COGS through higher first-time-right rates, effectively improving productivity by reducing error-handling labor time. However, this improvement could also be categorized as non-value-added work reduction. Both are correct, but you should count this value contribution in only one category: either non-value-added work cost reduction or reduced opportunity for error cost reduction.

Real firms' financials include additional revenue and cost categories (interest, debt servicing, M&A activities, write-offs, etc.), but these are typically extraordinary one-time events and/or minor relative to overall firm performance.

Risk can be quantified by summing all avoidable costs associated with risk events occurring over the past 24 months.

Every organization incurs risk associated costs every year. However, these costs are often disguised in other functions' financial ledgers. The risk of a bad accounts payable process is born by late payment fees born by the purchasing business line, not the A/P team. The risk of regulatory penalties due to erroneous reporting is paid for out of corporate contingency reserve. The risk of bad customer service requiring an avoidable one-time customer discount to recover the customer relationship is hidden in future sales discount rate and lost revenue. But all of these are real costs to the corporate ledger.

Every C-suite executive has learned to be skeptical of technologists' value claims. They have been burned before or seen peers' careers derailed by failed technology implementations and unmet business outcomes. Every C-suite buyer viscerally understands that technology programs' value delivery requires coordinated people, process, technology, and data inputs. Technology sales professionals immediately discredit themselves with opening pitches claiming "Our technology will improve your EBIT by x%."

The full value realization journey will be covered in another article.