Tech Programs' Value Lifecycle

The five-phase value lifecycle framework anchors technology value claims in a value realization methodology, increasing business buyers' confidence in realizing the value of a technology investment.

The technology value lifecycle is the framework for aligning technology investment value claims with funding business sponsor expectations, joint accountabilities, and continuous improvement.

First article in the Value Lifecycle series

CIOs, enterprise architects, tech consultants, and software sales executives must all be value sellers to convince CFOs to allocate scarce capital to any technology investment. Crucially, value sellers need to convince funders that the value potential can actually be realized. Key to this is a coherent value lifecycle methodology that defines the steps from goal and need articulation, to value identification, to value realization.

The end-of-program value realization "audit" is the most important phase of any program.

This paper describes the phases of the value lifecycle. This value lifecycle framework (and visual) is the anchor for the multi-part value lifecycle "how to" project. It contextualizes and locates the subsequent papers that detail the phases and concepts in the value lifecycle.

[For simplicity, this document uses the term program. Programs are collections of related projects that collectively contribute outcomes and benefits aligned to the organization's strategic objectives. Yet, this framework is equally applicable to more narrowly focused individual projects.]

Transformation Program Value Lifecycle

A transformation program value lifecycle consists of five phases, with two subordinate feeder activities and two feedback loops (Figure 1).

Goals & strategies

Business leaders set goals for organizational performance improvement and identify strategies to achieve those goals. These strategies require investment of scarce resources: capital, leadership time, and staff capacity. Goals and strategies are often informed by leaders' vision and ambition and by two external inputs:

Industry benchmarks and disruption provocations: What is the competition doing? What should we be doing differently?

New technology capabilities: What value opportunities emerge from the latest technologies? How can we exploit these for competitive advantage?

Value identification

Vision, ambition, competitive pressures, new technology-enabled opportunities, and process improvement discoveries collectively identify a portfolio of value potential hypotheses. This idea generation phase1 occurs when business challenges IT to implement their vision and IT brings new technology-enabled ideas to the business.

Of all strategies and investment ideas identified in this portfolio, scarce resources (cash, time, focus, and political capital) permit only the highest expected value2 payout ideas to move forward in any funding cycle.

The highest value idea hypotheses require more detailed business cases.3 Thus, the idea portfolio is filtered to select few options for in-year funding consideration - the highest yield investment bets.

The early value identification phase hypothesized value. The late value identification phase formalized business case value estimates.

Program design

The program's purpose is to deliver the full, expected, measurable value established in the business case. It must be designed as such.

The select few value ideas that progress to in-year investments require a program design that optimally matches program cost, risk, and outcome delivery confidence. The program design - or program operating model - includes these essential elements:

Program goal, vision, and success definitions

Progress tracking and expected vs. actual value realized reporting

Governance roles, responsibilities, decision rights, input rights, and accountabilities

Resource allocations and tracking - internal talent, external contract talent, and capital outlays

Work planning, scheduling, coordination procedures, tools, and training

Issue and risk management procedures, tools, and training

Program tracking, reporting, and escalations

Technical infrastructure for software development, testing, and releases

Stakeholder management and communications strategies, procedures, tools, and training.

The standardization-to-customization ratio of the program operating model is determined by the program's size, duration, complexity, and risks. Simple programs may use off-the-shelf in-house standard methods. Complex, multi-year, "bet the company" programs may require tailored designs and methods.

Program execution

Program and project-level execution is straightforward. It executes the transformation strategies using technologies to deliver measurable outcomes minimally positive as those defined in the business case.

Programs do not end when technology is delivered. While the technical and organizational change work may be complete, the program itself is not done until the value realization phase concludes.

Value realization

Value realization is the "show me the money" phase of the value lifecycle. Executives make an investment and later judge that investment's performance.4

The early value identification phase hypothesized value. The late value identification phase formalized business case value estimates. The program execution phase may have refined the expected net value of the program. But ultimately, after technology implementation and after business operational designs, job functions, and talent models have adjusted through planful change management, the business sponsor and CFO will ask: "Did we get the value we expected?"

Value realization is the end-of-program reckoning of planned vs. actual value captured.

Value realization is the most important phase of the value lifecycle, regardless of the results.

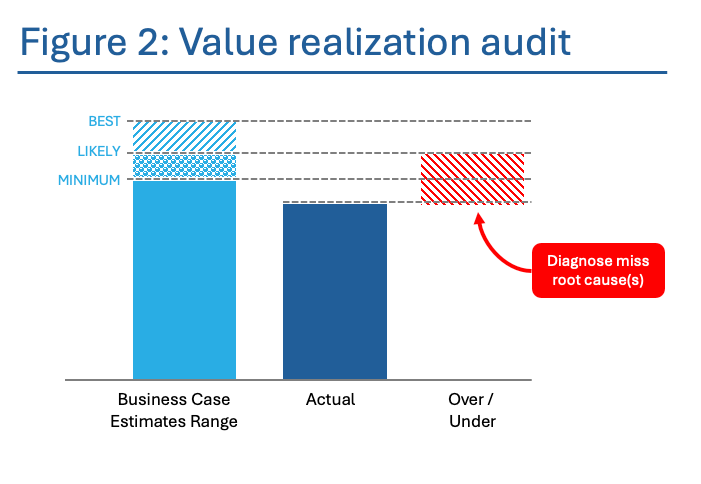

If the expected value (or more) materializes, that validates the quality of the entire strategy-to-value identification-to-execution program lifecycle. If the full expected value is not captured, as shown in an audit, that signals a need to diagnose root causes and learn (Figure 2).

Learning and improvement

Rarely does life go as planned.5 Agile philosophy teaches us that the answer to real world uncertainty is not more planning, but faster learning and adaptation to unanticipated circumstances. Quick identification, diagnosis, and incorporation of learnings back into the program's day-to-day "fast twitch" musculature and overall program design "slow twitch" musculature is critical to program full value delivery.

Fast Twitch Learning

Some learnings require "fast twitch muscle" responses to immediately adjust program procedures - for example, when cross-team communications fail or agile sprint work estimations prove unacceptably inaccurate. These are typically project-level improvements.

Quickly identifying anomalies, diagnosing them to root cause, solving the root cause, and rapidly incorporating the learning into the program operating model is essential.

Slow Twitch Learning

Some learnings require "slow twitch muscle" responses to redesign the program operating model - governance, team structure, value modeling, and investment portfolio selection methods. These are typically program-level improvements.

The biggest and most typical program-level failure and learning opportunity is value estimation vs. value realization. Literature is rife with business leaders' perception of technology-enabled transformation program "failure":

70 percent of transformations fail - McKinsey

At least 40% of recently implemented ERP initiatives disappoint business stakeholders - Gartner (2023)

55% to 60% of ERP initiatives fail to meet stakeholder expectations - Gartner (2018)

Only ~30% of organizations achieve successful digital transformations - BCG

Most automation transformations fall short, despite opportunity to reduce costs by as much as 30% - Bain

Most investment ideas will not yield their exact expected value, as defined in the business case. That is typical. But the program must learn from the variance and adjust. To avoid repeating history, each program must formally ask:

Was the variance acceptable? If not, why not?

Was the business case model wrong?

Was the tech team overconfident in what they could deliver at what price point?

Was the business line overconfident in what cost savings or other value improvements the new technology would support?

Did the sponsoring executives fail to hold external stakeholders accountable for their part of the transformation?

What assumptions and estimates proved wrong?

This is a core function of program governance - to track progress against plan and interrogate deltas real-time and at the program's end.

Plan vs. actual variances over time and the answers to the above diagnosis questions should be tracked with the same rigor as budgets and technical defects.

A project value delivery miss is a tactical failure. Not incorporating lessons learned from that miss is a strategic failure.

Program governance and change management

Program governance, at base, defines decision rights, input rights, and accountabilities.

Decision rights and accountabilities must align, because you cannot hold a person accountable for something she cannot control.6

Accountability

The overarching duty of program governance is to hold responsible parties accountable for delivering on their commitments. These commitments include resource (capital, talent, data, access) delivery, work product delivery, quality, and timeliness.

Accountability governance is an active behavior, requiring executive sponsors' time, focus, and willingness to probe anomalous and unexpected conditions.

Central to accountability is ensuring value delivery commitments and stakeholder alignment to program goals, outcomes, change impacts, and in-flight resource contributions through change management.

Value Accounting

Central to program governance accountability is value accounting. What does the business sponsor consider valuable and how is that measured? Value accounting is crucial because you cannot hold people accountable without agreement on expected outcome metrics and levels.

Value accounting is wider than cost accounting,7 as it can incorporate value goals beyond currently budgeted costs. If a firm is in a retrenchment period, pure cost takeout may be the only relevant value calculation. If the firm is in a growth or investment period, then other value categories besides currently budgeted costs may be important to executive decision makers.

Essential to transformation program governance is agreement between the business sponsors and the program delivery team on the value categories and accounting methods. Failure to do this with sufficient transparency and precision inevitably results in the missed expectations and "failed program" judgments detailed above. To be clear, some programs are deemed failures because they actually failed. However, rigorous value accounting discipline prevents successful programs (from the program team's perspective) from being deemed failures (from the business sponsors perspective).

Value accounting vs. cost accounting will be covered more deeply in a separate article.

Organizational change management

Organizational change management (OCM) is central to any technology-enabled business transformation program success and at the root of most transformation program failures.8

Central to the program failures documented above is missed expectations. Missed expectations evidence a failure to communicate clearly, precisely, frequently enough, and by methods and language comprehensible to all stakeholders - and to listen to those stakeholders' feedback.

OCM is too large and nuanced a subject to cover here, but readers can start with John Kotter's work. At the highest level, OCM starts with inventorying all program stakeholders, identifying the program's impact on their work, roles, and assumptions, and defining strategies for engaging each stakeholder group in two-way communications regarding the program.

Part of this two-way communication is "pulse checks," where the program listens to the various stakeholder groups as to their understanding of the program's purpose, goals, measures of success, changes impacting them, expectations of them, and schedule. This serves as a feedback loop to the program to assess if program messaging is successful and where expectations are misaligned.

For the purposes of the value lifecycle, the two-way communications is with executive stakeholders and focuses on the value accounting described above. CIOs can pose a simple prompt to the program's business sponsor to test their level of mutual program expectations:

"In your words, tell me what you expect from this program, how you will measure it, and when you expect the results to be final."

If the CIO doesn't hear her/his own words repeated back nearly verbatim, s/he has an expectations problem.

Value Realization "Cone of Uncertainty"

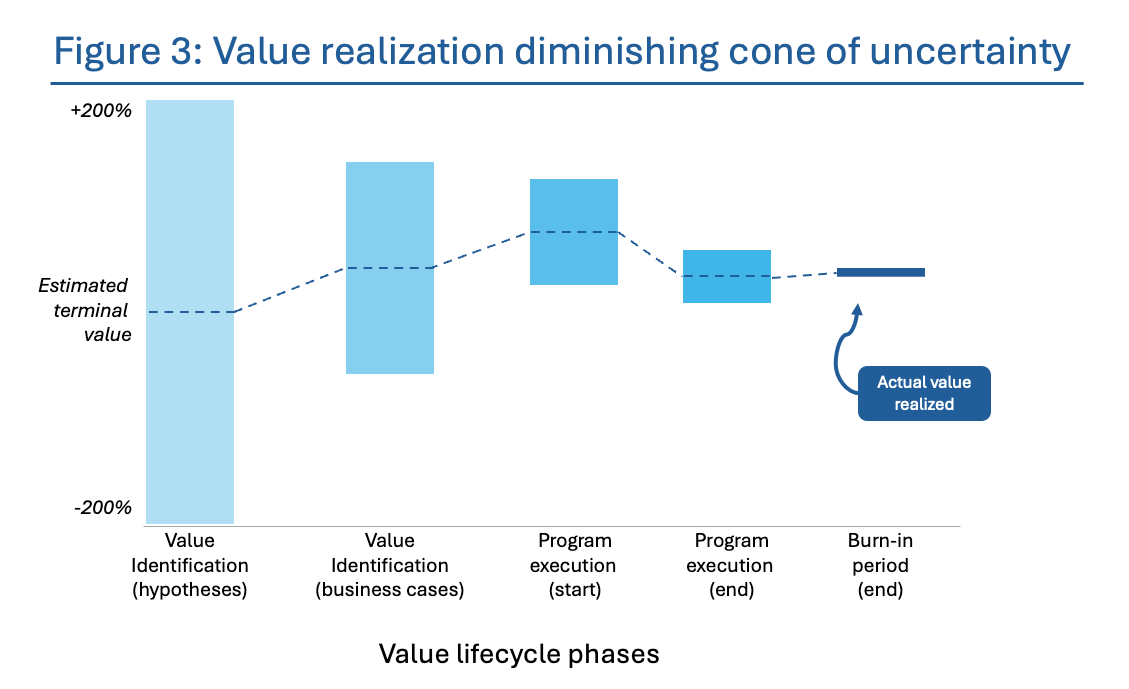

Project value delivery estimates are fruitfully viewed in a cone of uncertainty - just like other investments. No one can predict the future, but smart planners can reasonably estimate it.

Like other investments, technology-enabled business transformation programs are investment bets with probabilistic value payouts (expected terminal values). Because tech programs are finite in duration -- as defined in the original business case -- they have a definitive moment of reckoning when their actual realized value is known. Prior to that time the value to-be-realized is only estimated with decreasing levels of uncertainty (variance) through time.

Technology program business cases are estimates that gain precision as the program progresses toward completion. Smart value sellers are honest about this with the business sponsor executive and in the business case.

Figure 3 illustrates the narrowing business value variance to be realized across the value lifecycle.

Initially, business value estimates are rough orders of magnitude on either side of a terminal value estimate. If the idea's initial value estimate warrants prioritization and refinement, it moves to further discovery and design and a formal business case. As the investment progresses through the lifecycle, more value, cost, and risk information is known, allowing for more precise terminal value estimation.

Hence the estimated terminal value moves up or down and the likely range of variance narrows as the program lifecycle advances. Once the technology program is completed, there will likely be a short burn-in period for business operations, processes, volumes, talent, and budgets to adjust and be reallocated. The final business value realized assessment (audit) comes at the program governance-specified burn-in period end.

Conclusion

Value selling without a value realization strategy is just a "sales pitch." A clearly defined value lifecycle framework is essential to instilling confidence in executive sponsor / technology program funders in the feasibility and likelihood of technology value claims.

Use this framework as the "we are here" map in communicating the value opportunity discovery, prioritization, execution, and value realization lifecycle journey.

Subsequent articles will elaborate on the lifecycle phases, concepts, methods, and artifacts necessary for managing technology-enabled business transformation programs.

This is the divergent thinking moment in Design Thinking terms: "Why not …?"

Expected value is the likely return on an investment taking into account all possible outcomes and their probabilities.

The value identification "idea" or "hypothesis" level business cases are limited to order of magnitude value and cost estimates.

The highest expected value hypotheses then get a more detailed solution design and associated cost analysis and a more detailed value potential specification. In the fast moving agile world, these detailed business cases will still be directional -- perhaps +/- 25%. Importantly, the business line owners must agree to the business value calculations. If IT delivers the technology as anticipated, then the business needs to be accountable for the process, personnel and budgetary changes required to deliver the business case value.

Importantly, business cases must include costs, benefits, and the accrual timing of both. Every technology program must have a "pencils down" moment when the test (hypothesis) is done and value realization grading begins.

Many technology programs’ terminal — or exit rate — value is only know after a period of new business model stabilization and changes afforded by the new technologies. This “burn-in period” may last weeks or up to two quarters. It is important the business case models define the mutually agreed burn-in period before the final value realization audit and that the business case accounts for accounting anomalies due to arbitrary fiscal period ends.

Don’t let the fiscal period end reporting wag the value realization accuracy dog.

Pick your favorite planning quote:

“In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable," - Gen. Dwiight Eisenthower.

"No plan of operations extends with any certainty beyond the first contact with the [enemy]," - Gen. Helmuth von Moltke.

"Everyone has a plan 'till they get punched in the face," - Mike Tyson.

Using RACI chart language, the responsible party does the work and is responsible for the quality of his/her work. The accountable party controls all the decisions, resources, and talent required for the responsible party to complete his/her work.

Most firms have a finance-department mandated IT project business case Excel template, that ultimately produces ROI, IRR, and payback period calculations. These are typically narrow cost accounting models, that define value exclusively as reductions in current year budget lines. Under business downturns, this may be the only value that counts. At other times, harder to measure and model values of risk reduction, quality improvement, speed improvement, and less management distractions may be strategically important and valuable.

See the above missed business sponsor expectations citations. Typically, governance and organizational change management are the root causes, not technology.